How to Solve Common Teenage Problems–Disobedience, Disrespect, Disregard

The years of adolescence present many common teenage problems. Many parents of teenagers feel like they are constantly yelling at their teens for something they did or didn't do. According to Anthony E. Wolf, Ph.D., a practicing clinical psychologist and author, "Of course, the reason for so much conflict is that we make requirements of teenagers--take out the trash, clean rooms, get up on time in the morning, be home by a particular time--and very often they don't do it."

The years of adolescence present many common teenage problems. Many parents of teenagers feel like they are constantly yelling at their teens for something they did or didn't do. According to Anthony E. Wolf, Ph.D., a practicing clinical psychologist and author, "Of course, the reason for so much conflict is that we make requirements of teenagers--take out the trash, clean rooms, get up on time in the morning, be home by a particular time--and very often they don't do it."

Conflict sometimes happens because (although they'd never admit it) teenagers don't want to grow up. An excellent way to keep connections with parents is to have constant battles. Dr. Wolf advises, "Parents must see these wars for what they truly are--desperate measures on the part of the child's baby self not to let go."

As parents of teenagers, you must learn to avoid getting trapped in this unpleasant and potentially harmful dynamic. The secret is to know how to end such "discussions."

Your teenager is testing you when he tries to pull you into a battle. Parents must know how to limit conflict to what is necessary and avoid battles that are pointless and needlessly exhausting.

"Greg, clean your room."

"I can't. I'm busy. (He's watching Sports Center on ESPN.) Quit hassling me."

"Linda, we expect you home at your usual curfew."

"Forget it! There's not a chance I'm leaving this party early."

The parent wants one thing and the teenager wants something else. As Dr. Wolf says, "The child is being asked to do what he does not want to do. More basically, he or she is being asked to accept a loss–not getting his or her way." Linda wants to stay out late. Greg wants to maintain his current level of comfortable passivity. In order to get what they want, they are prepared to fight with you. They will keep it going as long as you will, or until you give in and let them have what they want.

What Can You Do? Consider A Possible Dialogue:

After giving clear explanation for Greg to get to work and Linda to come home...

"Greg, do it now."

"Linda, I expect you to be home at midnight."

This needs to be your last line. No matter how much you want there to be more to the script, you must stop now.

"Get off my back! I'm not doing it!"

"You can ground me for the rest of my life! I will not be home by midnight tonight!"

STOP! Squelch your desire to reprimand this defiant display of willful disrespect. Everything in you may be screaming for you to verbally let your child have it. You have a lot you know you could say. Force yourself to turn your back and leave the battlefield.

Cause the Teenager to Think

The result of this action is that your teenager is left with your last, calm, powerful phrase hanging out there. ("Do it now," or "I expect you to be home at midnight," etc.) These are the words that are reverberating in your teenager's mind, rather than hysterical, foolish-sounding retorts to the words that were meant to draw you into the conflict. If you had fallen victim to your teenager's desperate attempt, he or she could have kept things going for quite some time. According to Dr. Wolf, "Teenagers do not consciously plan to keep the battles going. It just comes out: the ever-present voice of the baby inside who does not want to let go. For if the argument ends, the baby is alone. . . . If alone, with no parent to fight with, the child's debate becomes internal."

...Linda will wonder if she really wants to chance staying out past curfew. You sounded pretty serious when you said you expected her home at midnight. She will consider whether staying out late is really worth the trouble and the potential forthcoming consequences.

...Greg will be left to consider whether he should actually extricate himself from the couch and accomplish something. He will debate the point with himself because he can't continue to fight about it with you. He will be forced to contrast his lazy, whining behavior with your composed, "no nonsense" demeanor.

You may be thinking you can't let your teenager "get away with saying that," but force yourself. As long as teenagers can keep in contact with you, even through backtalk and arguing, they will attempt to do it.

When Teens Disobey/Disrespect, Again–Win the Battle of Wills...By Not Playing the Game

Disrespect or open disregard is another common teenage problem. If your son, in fact, does not clean his room, or your daughter comes in at 3:00 am, you must now impose a punishment. Your teenager may try to regain some power by saying, "I don't care. Do whatever you want." Don't fall into the trap of feeling like you have to add more and more to the punishment in order to get your teen to care. He does care. He's just saying he doesn't.

If you make a requirement and your teen expresses her intent to disobey, saying, "I'll do whatever I want," or "No way will I do that," don't keep this battle going either. Your teen is willing to risk saying she will or will not do something. Carrying out the disobedient act is another matter. Dr. Wolf advises, "Having already stated their position, parents need say no more. They should deal with disobedience only when and if it happens. They should ignore all mere threats of disobedience."

Lecturing Teenagers Does Very Little

Most parents come to realize that lectures do very little good. Dr. Wolf says, "Only one good reason exists to rave at one's child: it makes us feel better. We should not delude ourselves as to who it is that benefits from our lectures." Insist on your original, simple request. Don't get sidetracked by your impulse to lecture.

Even as adults, we want to get the last word or even the score. It's extremely difficult to just drop it. Usually our reasons for keeping the conflict going have to do with our desire to "not let them get away with it." "But," according to Dr. Wolf, "if our aim is not to get caught up in lengthy battles, if our aim is to have them learn something positive, then, almost invariably, the greatest wisdom is simply to shut up. By going on, we teach them only one thing: we want to be in control. And the scene invariably switches from the issue at hand to a battle of wills."

Reference

Wolf, A. E., Ph.D. (1991). Get out of my life, but first could you drive me and Cheryl to the mall? New York: The Noonday Press.

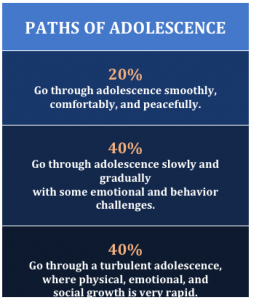

Forty percent of teenagers experience at least some emotional and behavior challenges. Click here for solutions to common teenage problems.

Forty percent of teenagers experience at least some emotional and behavior challenges. Click here for solutions to common teenage problems.

Forty percent of teenagers experience a more turbulent, rebellious adolescence. Click here for solutions to rebellious teenagers.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed